In this chapter, Ed Bryne takes us through the process of designing a simple level of a game. There are many basic and critical elements which should be put into place for the level to be fairly simple and easy to figure out, whilst still keeping the player feel like they accomplished something challenging.

Level Design Building Blocks

The basic elements of a level, or the "building blocks" are these:

- Concept

- Environment to exist in

- Beginning

- Ending

- Goal

- Challenge to overcome between the player and the goal

- Reward

- Way of handling failure

Although these building blocks don't cover more complex elements which you would find in a modern-day shooter or RPG, they generally work with most modern games, you just need more of everything.

A good example of this method would be a Tetris-style puzzle game, as it's still a very popular template for modern games:

- Concept: Find a place for the blocks or lose the level.

- Environment: The active play area to the left of the game data.

- Beginning: The player starts with an empty screen and a score of 0

- Ending: The level is over when the player either creates the correct number of vertical lines (success), or the blocks pile up to the top of the screen (failure).

- Goal: Create a number of lines that meet the target requirement for success.

- Challenge: The speed of descent, type of blocks, and number of lines needed.

- Reward: The player moves to the next level, or receives a brief animated sequence.

- Failure: The game ends and must be started from the beginning.

Story

Storytelling may seem important, but it isn't a fundamental requirement. Story can enhance a level and give players information about what they're expected to do, but many games exist without a narrative element. Players are left to imagine their own story, for example in chess, which has elements of medieval war and politics, but can also be played with coloured stones.

The gameplay drives the game, and is what drives the stages and levels within them. Ideally a game should allow players to create their own narrative as they play, even if it's just a list of personal achievements.

Putting the Elements Together

Concept

As the example, it is a game for a portable phone called Clownhunt; it involves the player controlling Crispy, a clown escaping from an insane ringmaster.

The player can move Crispy left and right and make him jump, he can fall from any height, has unlimited energy for jumps and has no inventory or weapons. The game is simple.

Environment

Clownhunt is set in a circus, all elements should be thematic. "Cartoony" graphics fit well and offer contrast to the games context, running from murderous ringmaster.

The environment consists of static background, starting point, visible exit and whatever elements to help him in the foreground. There isn't a HUD to interfere because the game doesn't have lives, energy or other "metrics".

It's also important to keep the player immersed in your game by keeping everything to the right theme, but it's also important because the player needs to understand what they can and can't do. If you were to drop a pair of wings in for the player to put on, he will obviously believe he's able to fly.

Beginning

Begins with the player on left of screen ,he needs to move to the right to reach exit. Entrance can be at the top, the middle or at the bottom of the screen, depending on the level. This level starts at a plain wooden door next to elephant cages.

Ending

The exit needs to be far away to make it more challenging, the exit is therefore placed in the opposite corner of the entrance, and clearly labelled 'exit', to make it obvious for the player.

Goal

The goal in every level of Clownhunt is the same - reach the exit. Other elements can be added, but for starters it doesn't matter. It's important for the player to be able to finish the level.

The game has a narrative-driven goal, as although Crispy is supposedly running from the Ringmaster to motivate the player to continue, the Ringmaster will never actually appear in-game. This means there is no need to precede each stage with a description of the objective, and also no need for additional metrics.

Challenge

This creates the fun in this level, we need a challenge to stop the player simply reaching the exit, but it needs to be thematic - that it doesn't seem out-of-place or goofy for the genre of game. This is called

dissonance, it has to be avoided.

A seesaw would be good as it fits with the game style, and it is useful for a number of reasons:

- The player needs to gain height to reach the exit.

- It is immediately recognizable by most players.

- It's easy to see how it works from looking, so no explanation is needed.

Determining the Challenge Mechanics

We now have to add mechanics that allow the player to interact with it, we can usually break down challenges such as this into different sorts of mechanics.

For example, the mechanics behind doors are simple in most games - activate a door and it will move on one axis (usually hinges), as in real life. The best gameplay mechanics need no explanation, allowing players to interact with them from their own observations. This makes players feel clever and allows the designer to stay out of the picture.

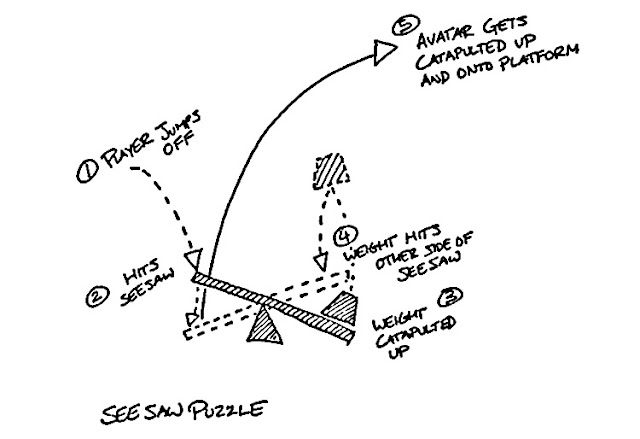

The seesaw mechanics should work as the player expects, a weight on one side makes that side go down, and the other rise. There are three possible ways to do this, as illustrated:

To avoid adding any new gameplay mechanics into the game, the only way it will work is if we put the weight ON the seesaw. Crispy can only move left, right, and jump.

By putting the weight on the seesaw, it means players need to work out how to use it to throw the weight up, then use resulting impact to propel Crispy to the exit. This mechanic needs little explanation, as players know how gravity works.

The player feels obliged to then jump on the high part to make the opposite weight fly up, smash down and send him flying. In real life this wouldn't work, it might break the seesaw or the weight may not land where it started, but this is an example of "game logic". Game logic means events may be more predictable than they are in real life.

Knowledge about the game, gained within the game itself is called intrinsic knowledge, whereas knowledge applied in the game but gained from another source, usually real life, is called extrinsic knowledge. With the seesaw, the player uses his extrinsic knowledge of how it works in real life to tackle the virtual problem.

It's good to include a simple set of in-game rules for objects to follow and react to the player's actions. It's useful for the programmer to implement these when they code said object.

An example of a rule for the seasaw would be:

Multiply the distance the weight goes up by the number of feet the player character falls before landing on the other end of the seesaw

We then add a pile of objects in front of the seesaw for the player to get high enough before jumping onto it, as he currently can't jump high enough without them, and we don't want to alter the functions of the game.

Reward

The main reward for completing the level is access to the next one, and a secondary reward would be a short victory animation of Crispy giving a thumbs-up. For many players, the act of completion and progression is the driving force for playing a game.

Failure

What happens when the player fails is another important aspect. With this game this is handled inherently, there isn't a timer or over-arching challenge that ends the game before the player finishes.

In this level there is no way for the player to fail, and the more players can blame the designer for failure, the easier it is to simply stop playing. Because of this, it's good to let the player have a way of climbing back up and trying again, instead of kicking them out and forcing them to retry.

My Thoughts

This chapter made it very clear that a lot of different genres share the same basic elements that make up the game, and that by learning these building blocks, it's possible to make a basic design for almost any kind of game. I thought the order in which he set up the level was quite interesting, as it involved planning out the start, finish and general level layout before thinking about the challenges. Personally, I think it would be good to think of a set of challenges to overcome and generally base a level around said challenges, to make them seem more coherent with the theme of the game and fit perfectly.

The information and techniques discussed will certainly be helpful in the future.